This article appeared on the Hub. For insightful dialogue, visit the Hub at www.thehub.ca

From flat earthers to 9/11 truthers, the world has seen its fair share of conspiracy theories. During the past two and a half years of the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories abound with people questioning the legitimacy of the state, from both the too many restrictions flank AND from the not enough restrictions perspective. The state, simply put, could not win. That’s if you listen to the echo chambers of social media and ignore the electoral reality that most governing parties in Canada were re-elected during the pandemic.

Conspiracy theories are a special category of thoughts that have permeated our regular discourse. There’s a whole anti-vaxing underworld committed to proving that we are being hosed by the likes of Bill Gates who, as some have claimed, masterminded the entire pandemic. Websites exist that discuss the vaccine as poison and some even try to track the lot numbers of the vaccine to determine whether the injection an individual received was in fact a placebo.

On the other hand, COVID-Zero proponents created an impressive online infrastructure extolling the virtues of completely shutting down life as we know it with the purported goal of making sure nobody got a viral infection. These folks are inclined to believe that government scientists and public health officials were making politically motivated decisions rather than keeping society as safe and as free as possible without overwhelming hospital infrastructure.

Everyone knows somebody in either of these two camps. There are countless stories of families who have literally been torn apart by taking sides during the pandemic for making whatever choices they wanted to make. One side felt hurt that the other side was acting stupidly. It doesn’t matter which side I’m speaking about. The one side always thought the other side was acting irresponsibly, and the differences were so significant that they were hard to reconcile.

The question that begs is this: why do people view the same situation so radically different?

In the book, Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing our Own and Other People’s Minds, Howard Gardner points to a few things that are important to acknowledge about the human mind. The first is that people hold on to their views because it feels psychologically safe. Our brain is preconditioned to think in terms of “us” versus “them.” We are predisposed to think about belonging to an “in” group versus an “out” group. We find attachment to what the “in” group is versus the “out” group based on feelings we develop about the situations that we are in. The “facts,” in this instance, are trivial. Emotional attachment to “belonging” is an important criterion to understand.

Ever try to get into an argument with somebody by giving them a bunch of facts of why your take is correct only to be met with a person completely unwilling to bend to the stack of evidence you have presented? While we tend to think that we are all reasonable people who reach conclusions by viewing the preponderance of evidence before us, we encounter people in our everyday lives that are polar opposite to our views who also believe that they are convinced by the preponderance of different evidence before them. We are even bound to think that if everyone was just as smart as me, they would reach the same conclusions. Yet, they don’t!

Gardner makes a different argument about the way the human mind actually works, which may help explain why people view the same situation differently. He says that we actually do not gather evidence and then make a decision based on where the information takes us. The opposite is, in fact, true. People make an emotional decision about how they feel about a situation and then use evidence to support their perspective.

The visceral reaction I am likely to encounter by stating this point, as I have with many points I have made during the COVID-19 pandemic, will only serve to reinforce how correct this take is.

Now that we know how the human mind works, let’s now discuss how every pandemic known to humans has been met with the most amazing conspiracy theories.

In his book, The Psychology of Pandemics, Steven Taylor predicts much of what has transpired with the COVID-19 pandemic before it happened. He has a useful chapter on conspiracy theories that offers many reasons why conspiracy theories are prone to happen with every pandemic.

Taylor explains that disease outbreaks commonly bring about conspiracy theories because the nature of the disease is poorly understood. Taylor points to a study that looked at medically unsubstantiated conspiracy theories in the United States that found between 12 percent and 20 percent of respondents agreeing that certain conspiracy theories had validity.

People who believe one medical conspiracy theory are predisposed to believe in other ones. That means, before the pandemic even occurred, 10-20 percent of the population was predisposed to thinking that some nefarious actors were going to be responsible for a pandemic that radically altered their lives.

The aforementioned study found that most conspiracies were fueled by a lack of faith in government institutions, suspicion of multinational corporations propagating a crisis to increase profits, large philanthropic foundations that had more than altruistic motivations, and suspicion that medical experts recommended treatment known to cause people harm.

All of this must surely sound familiar for observers of news during the COVID-19 pandemic, and many of these conspiracies are likely to continue to be part of the post-pandemic narrative of what happened during the pandemic. The facts, whatever they are, are contestable, and that is unnerving to a lot of people.

In a study of conspiracy theories on social media, several common features are evident. An important one is that those who believe in conspiracies go to great lengths to cite supposedly authoritative sources to support their views. How many times have we heard that X medical doctor said this was unsafe, hoping that we’d all somehow change our opinions?

In addition, one of the principal perspectives is that the conspirators use stealth and disinformation to convince the masses to act in ways they otherwise would not. This makes falsification of conspiracy theories unsuccessful because those that try to debunk the conspiracies with “the facts” are considered part of the “brainwashing.”

Sadly, eliminating conspiracy theories during pandemics is virtually impossible. Understanding that they exist, and why, is important in determining how best to confront them. Changing minds is difficult, and restoring faith in institutions and information takes years to establish. The time to start work on this is now.

This article appeared on the Hub. For insightful dialogue, visit the Hub at www.thehub.ca

There are many things that were disturbing to many about the occupation of Ottawa and other places around the country by insurgents that encamped our bridges, communities, and nation’s capital. Make no mistake, the unsettling feeling we share is a direct threat to our democratic values.

Insurrections have happened many times throughout history. Our Founding Fathers were keenly aware of the possibility of militant groups disrupting peace, order, and good government. They deliberated extensively over the kind of government that would protect us best, and they carefully chose one that has so far withstood the test of time.

One of the major tenets of our parliamentary system is the idea that parliament should reign supreme. Parliament in the Westminster sense consists of Monarchy, aristocrats, and commoners all brought together under one institution: parliament. The underlying theory is that each part of parliament would act as a check against the other and that decisions taken in our society can only happen when all three are in accord. Yes, it is true that even unbridled democracy needs to be checked against the potential for majority rule to infringe on minority rights.

Parliament is said to be supreme, and it is important that it remain so. Dicey reminds us that parliamentary democracy is supreme because of four crucial features. First, it can make and unmake any law it pleases. Second, that no other institution can surmount the legislative will of parliament. Third, is that there is one law and that the rule of law promotes the idea that no one person or group is above the law. Lastly, periodic elections ensure that the pulse of the nation is checked at guaranteed intervals so that the will of the people is heard and understood.

Our Founding Fathers deliberated at length over what form of government they wanted for our country because they knew what they were trying to protect. One of the biggest sources of influence on them was the democratic experiment that was taking place in the United States. There, our British North American Act drafters saw potential for chaos. They witnessed rebellion and were concerned about factions developing and challenging the laws and the orders that had been established.

If you are reading this and thinking, “Hey, wasn’t this convoy a faction? Aren’t they challenging the laws and the peaceful existence of a section of land?” Why, yes, the convoy would fit the very definition of a faction.

The concern over faction has strong 18th– and 19th-century roots. Indeed, even the Americans were concerned about it. In “Federalist Paper No. 9”, Alexander Hamilton argues that checks and balances, along with strong central government, are essential to defeating factions within society. In “Federalist Paper No. 10”, probably the most famous of the Federalist Papers, James Madison goes into great detail about the importance of controlling factions.

Madison defines factions as “a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.”

Sound familiar?

Madison argues that there are two ways of dealing with faction: remove its causes or control its effects. He suggests that removing its causes is problematic because it is inherent in people that they will disagree, that they should be able to do so, and limiting people’s disagreement is worse than the problem of faction itself. We’ve been debating this problem with the invocation of the Emergencies Act.

That leaves us with controlling its effects. Here, Madison argues that representative government, not “pure democracy” (or what is more commonly referred to as direct democracy) is the answer. The reason for this is that the broader public elects people who are then expected to balance our competing interests to determine the common good of everyone. Sir Edmund Burke called this deliberation between interests—local, regional, and national—to be a central feature of those elected to legislative assemblies.

The need to eliminate faction is best done through representative government. A minority fringe hijacking the public agenda should not be tolerated. As Dicey says, parliament alone can make the laws. We all have to live with the laws that parliament makes. No one group or organization can replace parliament in making laws for any part of a country. And, if we’re not happy with the laws that are being made, we get a chance to vote the representatives out of office when the time comes.

Our freedom is linked to our democracy. Our democracy is linked to parliament and the virtues of representative government. A mob cannot be for freedom if it is against democracy.

This article appeared on the Hub. For insightful dialogue, visit the Hub at www.thehub.ca

As June comes to an end and high school students finish up their year, many of them are preparing to move on to higher studies.

The vast majority of students bound for higher education will be headed to Canada’s publicly assisted colleges and universities. A handful might head south of the border, where there is a mixture of publicly supported and private colleges and universities. However, very few students destined for higher education will enrol in one of Canada’s private universities. Those institutions haven’t flourished on this side of the border as they have in the United States and elsewhere around the world.

The question is: why haven’t they?

Sign up for free unlimited access.

In the interest of disclosure, I will say that I have extensive experience with the publicly assisted university system. I got my PhD from McMaster and worked as a full-time faculty member at both Wilfrid Laurier University and the University of Western Ontario. I had positive experiences at them, and don’t for a second say otherwise.

I have also worked with private institutions. I am currently a faculty member at Niagara University in Lewiston, NY, and have advised a private university startup at the International Business University (IBU). I have also worked with private career colleges and training institutes, language schools, and other degree-granting institutions. Each type of university I have had the privilege of working with has had its merits and its drawbacks.

However, private institutions in Canada are often unfairly painted with a particular brush: they are degree mills, anybody can get in, quality is inferior, tuition is sky-high, they are fly-by-night operations. It is as if American private universities do not exist — those same private universities that are ranked among the best in the world.

Criticisms levelled at Canadian private universities also often fail to acknowledge the challenges that can exist at publicly assisted universities: enormous class sizes, an overreliance on sessional adjunct instructors, students who are just numbers that fall through the cracks.

Publicly assisted universities have even had run-ins with financial insolvency (see Laurentian University in Sudbury, ON ). This, despite the fact that publicly assisted colleges and universities are supported by billions of dollars just to open their doors. Cost controls are difficult as faculty compensation continues to grow and full-time faculty teach fewer courses each year. In fact, the Council of Ontario Universities recently put that number at 3.2 courses per year for full-time faculty members.

Public and private universities each have their merits. Where one system has big classes, the other has small ones. Where one has higher tuition, the other system has lower. The point is that true choice requires a spectrum of offerings to meet the needs of students, society and the economy.

Take, for example, this story in the Financial Post. Businesses are concerned about the length of time students take to complete university degrees and about their job readiness once they graduate. This is an issue private universities are perfectly positioned to solve.

There are at least a couple of identifiable issues highlighted here. The first that degrees take too long, and the other is that students are not job ready when they are done. This was the genesis of startup IBU’s accelerated BComm in International Business and Technology. One of the key differences between the IBU program and its competitor business programs is that the IBU degree uses the traditional summer months for learning. Thus, a student can get a four-year honours degree in less than three years. Not bad. Also, the IBU program is moving toward competency-based education to ensure that its graduates have the skills employers want.

Is it for everyone? Not exactly. Lots of students like the summer months to earn a little money, travel, and recharge. However, there are students who want to get in, learn, acquire the skills and get on with working as quickly as possible. IBU’s program offers that option.

From a faculty perspective, the switch for me personally has been eye-opening.

While teaching loads are heavier (six courses per year is typical), the reality is that smaller classes allow faculty members to teach multiple sections of the same course. Therefore, whereas at Western I would teach one section of research methods with 100 students, I could teach fewer students over three sections at Niagara University and that would be my entire load for the semester.

The focus on peer-review of teaching is far greater at Niagara too — peer reviews that can have an impact on tenure decisions. I’m not sure there has been a semester yet where my dean and chair haven’t sat in on a course to provide feedback on my teaching.

Far from the common misconception, the focus on quality is high.

External accreditations authenticate and validate degree quality. In my experience, private institutions are focused on delivering quality and key performance indicators as a function of their recruitment success. I oversee the Teacher Education program at Niagara University’s location in Vaughan, ON. Our applications are high and are acceptance rate is low, comparable to many of the public institutions we compete with. In the case of that teacher education program, it is accredited by the Ontario College of Teachers like every other teacher education program in the province.

The point is not to say that one system is better than the other. Rather, we should be enabling choice. There is a predictability with public universities. Differentiation among those institutions typically is found at a program level, but the governance, structure, and approach has a fair degree of uniformity. It is also a system that is expensive and designed by its ardent supporters to keep wages trending higher and workloads trending lower.

With public dollars for those institutions waning, the focus becomes packing classes and propping up the financial bottom line with international students.

Providing more options for students to address their needs, as well as the needs of their future employers, makes a lot of public policy sense. Plus, the biggest benefit is that it opens up spaces in higher education without costing the government a dime.

This article appeared in the Hub. Visit the Hub for insightful dialogue: www.thehub.ca

At some point soon, there will be a reckoning of all that has transpired with government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The temperature and mood of the public gets captured in polling on an ongoing basis and public support for political leaders appears to be running short as the pandemic drags on day by day. The vitriol that we see on social media and the overconfidence of some medical experts are making a mess of citizens trying to understand where we need to go and how to get there.

In the midst of this, some other academics — ones who study government, for example — are trying to figure out where the fault lines lay and how we might be governed better beyond the daily grind of watching as our political leaders are seemingly failing us.

The first hot take is this: our political leaders might be failing us, but they aren’t doing so intentionally. Everyone will have their opinions about whether we could have done more or might have done something different, but all the decisions made by governments, as well as all sorts of organizations that have to deal with COVID-19, have been taken with painstaking care and hours of deliberation.

In fact, the truth of the matter is that public opinion and academic opinion on what to do are not unanimous. When they are split, the level of consensus on decision making is miniscule. There will only be a small fraction of the decision area where all sides align. Everything else is up for debate.

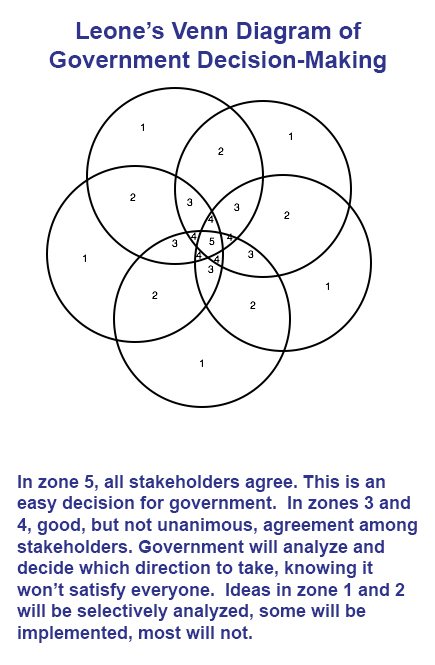

Take this Venn diagram of decision making. Here, we have five distinct groups of roughly equal size in the decision-making arena. Intersecting the circles shows the area of consensus. The number five denotes areas where all five groups agree, whereas the number four shows areas where four groups agree but one does not, and so on. This diagram serves to illustrate the point that when one group of experts, say the medical community, are advocating for things in which only they agree, it becomes a source of consternation for government because the four other groups aren’t on board.

But, the crazy thing about social media is we elevate those MDs and data scientists to a level where their opinions, because they are experts, are taken as sacrosanct. However, reality is different. There are other influential people talking to government who are experts in their own right: economists, workers, employers, and more. Whether one cares to listen to these ideas is not as relevant as the fact that governments obviously do. To do only what a narrow group of medical experts want would invalidate the pluralism of expertise that actually exists.

We will leave it up to the commentariat to determine whether a government should in fact be listening to one group over the other, but an objective viewpoint cannot help but understand that many different people and groups are feeding into the government decision-making process.

The important point to take away from this Venn diagram is to understand that governments are pulled in different directions. Governments know that they have to quash the COVID-19 virus, but they do not know the best way of getting there.

Lo and behold, there is actually a decision-making theory that explains this predicament. Robert Behn calls it the “groping along” model, which is also known as a form of management by experimentation. According to the theory, a leader who “gropes along” is not an incompetent decision-maker. Rather, the decision-maker knows what to do, but there isn’t a precise path on how to get to the goal. It suggests that, at any given moment, the manager has several decisions that could be taken to change the organization.

A decision-maker may be able to get closer to his or her desired end through a particular decision, but sometimes will be further from that end because of the negative experiences encountered along the way. When the decision-maker realizes this situation by analyzing the organization’s environment, other steps will be attempted to get back toward the desired goal. This is how “groping along” works. The decision-maker knows where he or she wants to go, but might get lost along the way.

Put it in a different way, if a leader encounters a problem, he or she attempts to fix the problem. And, while the intent of fixing the problem is sincere, the outcome of the decision may have misfired. Sometimes, those decisions helped move the organization closer to the goal and sometimes they move them further away from it.

Now, if we go back to that Venn diagram where many different experts are providing compelling and often diverging advice, it sets up the perfect circumstance for a leader to “grope along.” When one approach fails, a leader has to start fresh and make another decision. When a different approach leaves other influential groups feeling unheard, the government tries to take into account those concerns in order to demonstrate that it is, in fact, listening to the pluralistic expert opinion that is present.

Straying from the initial course to listen to affected groups and their advice may be seen as “not learning” from what worked and what didn’t work in previous waves, but it should be seen as experimenting with other approaches, which are invariably also backed by evidence, to determine whether they might work better.

When Ontario Premier Doug Ford apologized for getting it wrong, he laid bare what was plainly obvious. He got it wrong and he failed.

And, after 14 months of refusing to impose a serious restriction on international travel, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government finally got around to doing some of it. Again, some approaches were tried with success. Others were tried and failed. Opponents clamour at the seeming incompetence and governments claim to be acting in good faith and for the health and wellbeing of people. Here’s the thing about that juxtaposition: it’s possible that they’re both right.

While the calls for resignation for our political leaders are present, here’s another solemn truth: It doesn’t matter who is in charge, those new decision-makers would be experimenting as they go along. The reason is that there is no playbook for dealing with the pandemic. Sure, the Conservative Party of Canada might have shut down international travel sooner, but they probably wouldn’t have been as quick on the income supports earlier on. It is possible that the NDP in Ontario might have enacted sick pay (or never gotten rid of it to begin with), but they probably would have been reluctant to enact executive orders to break collective agreements that allowed workers to be moved into sectors hard hit by COVID-19. We might praise somebody else for doing something different we like, but loathe them for entirely other reasons.

That’s what managing by groping along brings and after 14 months of dealing with the pandemic that seems to never want to end, it is entirely expected that we are fed up.

This pandemic has brought about government decisions amid a sea of potential alternatives. Without solid direction on how to get to where we all want to be — a Canada that is free from COVID-19 — our leaders try to navigate uncharted territory without a compass. They are bound to make mistakes, and, unfortunately, mistakes in a pandemic can be a matter of life or death.

To borrow a phrase from Trudeau, “better is always possible.” Unfortunately, it’s also true that worse is also possible.

There is a certain truth about Conservative opposition leaders. It’s the hardest job in politics. It seems nobody will give the leader credit until he or she wins, and even with the win, the honeymoon will only last a short while.

Why, you might ask? It’s because the current iteration of the Conservative Party elects a leader, and the very next minute, that leader is expected to follow the followers — followers who will ruthlessly guillotine the leader for non-victory while themselves escaping any blame for the cataclysmic failure. It is a Conservative form of Marxism, where the proletariat collection of members control the bourgeois party elites. It is the most perverse form of organization, and honest questions never arise so as to analyze whether it is working.

On social media, I recently posted a question that is relevant here. The question was quite seriously this: What was the last good idea to come from a Tory policy conference? The answers were few. Now, tell me how many embarrassing stories have come out of Tory policy conferences, and I am fairly certain the answer comes close to “there’s at least one every damn time.” Add to this the disdain of leaders ignoring member policy, and the fiasco comes full circle. Yet, nobody stops to say “hey, this thing is broken and we need to fix it.” Nope, see you in Quebec City in 2023. It’s a recurring story with as predictable a plot line as a Hallmark movie, except this is no love in.

Here’s another thing we need to know about policy. It’s complicated. Whenever a real government wants to implement policy, they typically undertake a lot of research and consult with those that might be affected by that policy. A government might even want to take the temperature of public opinion in crafting their policy. Is that the rigour undertaken by Tory delegates at this latest policy convention before they made a pitch for any of their given policies?

Take the above Venn diagram about government policy decisions. In any given area, different interests offer differing preferences. The Conservative party may well be only one of these circles. Leadership is about getting to areas of consensus (where all 5 circles intersect) or to where they might have support but need to make trade off (where 3 or 4 circles intersect). However, party delegates are mostly not capable of making tradeoffs nor are they interested in doing so. The name of the game is to get most delegates to support their own policies, even if nobody else agrees with those policies in the broader public. And, that’s fine to give the grassroots the voice, but we then take the knees out of the leader who needs to find consensus. Once a leader tries to compromise while half heartedly listening to members, the members turn on the leader for not listening to the grassroots. This is the death of leadership.

None of this is going to make me terribly popular with the grassroots, but there are many, many conservatives that need a forward looking, positive, ambitious plan to get Canada on the right track. We need a cogent, articulate and informed set of principles that says government need not grow endlessly, that cares about the safety of our communities, and commits to leaving our kids with a cleaner country than the one we inherited.

Erin O’Toole is the leader the party needs. Now we need to be the party that our leader needs.

Economists have been interested to determine what kind of recovery jurisdictions like Ontario might face by using letters to paint a graphical image for people to understand. In essence, a “V” shaped recovery signifies a steep halting of the economy with an immediate very quick rebound.

The 2020 Ontario budget seems to be telling us that we are indeed in a “V” shaped recovery. The first sense we get of this is employment. Between June 2018 (the last election) and February 2020 (the month before lockdown), the Ontario economy was humming, with over 300,000 net new jobs created in that period.

Of course, by May 2020, employment went off a cliff, having dropped more than 1.1 million jobs in Ontario alone, due to the economic shut down. Last week’s budget numbers suggests that by October 2020, almost 75% of the lost employment had been recovered.

Looking at the chart below, we can see the 2020 recession line displaying that “V” shape we have been hoping to see.

The GDP numbers appear to have a similar bounce. While there is considerable variation in private sector GDP forecasting, Real GDP is expected to drop 6.5% in 2020 and bounce back by a very strong 4.9% in 2021. Again, that signals a “V” shape recovery too.

What does this all mean? There were a couple of items we were looking for in the 2020 Ontario budget regarding economic development beyond the data. One of them was whether the Ford government would use the pandemic to abandon its previous objection to “corporate welfare”. There had been some degree of thinking that the government could engage in programs like the ones that emerged federally and provincially after the 2008 financial crisis – including, for example, possibly taking a public stake in large enterprises, other negotiated instruments to financially backstop large companies, or targeted government spending to give them a sharp revenue infusion.

This budget does offer support for businesses, but not in the way “corporate welfare” has historically been viewed. Rather than offer a specific program to fund economic development to specific recipients, the government instead has taken a broad-based approach from a tax perspective. The big-ticket items on this front consists of relief from the Employer Health Tax and reductions in property taxes for businesses. Rather than taking a very narrow focus with grants, the government has instead used tax policy to provide relief for all qualifying businesses. As a result, tens of thousands of businesses stand to benefit.

The other interest on the economic development front pertains to Invest Ontario – the government’s new economic development agency. The intent of the agency is to help market Ontario as a destination to invest and create jobs. It will compete with economic development agencies in Ohio and Michigan that were set up there to do much the same thing.

Making Ontario more tax competitive may be a key competitive differentiator. Invest Ontario is likely to base its pitch to prospective businesses based on currency valuation vs. the US dollar, red tape reduction, health cost savings, new tax measures, and a skilled workforce. Budget 2020 expands training and apprenticeship programs to help meet the needs of skilled trades jobs that are in demand. While the big grant programs are not available to Invest Ontario, some other aspects in Budget 2020 will be helpful as Invest Ontario seeks to attract foreign investment.

This is the first major government to provide a glimpse into how to manage the economic recovery. With a projected “V” shape, the government has chosen not to add additional spending in the form of grants to prop up job creation, as recovery seems to be occurring with the money currently circulating. With the election of Joe Biden as president of the United States, and his promise to significantly raise corporate tax rates, holding off on big grants at this time might just be the best policy choice. Ontario may become an even more attractive place to invest as a result.

Ontario’s school reopen plan is in trouble, and it’s not because the plan itself is terrible. I actually think the plan makes sense, but I am not a scientist. However, we once again find ourselves stuck on this science/politics nexus, and it’s eating away at the plan and its roll out.

During the pandemic, we have had this habit of listening to the science. We even celebrated the fact that politicians put their partisanship aside because they were following the advice of their top scientists and public health minds instead of political expediency. This school reopen plan followed that same idea with an even higher degree of vigilance.

As I wrote before, there are a few problems with elevating scientists to decision-maker, which is normally the politician’s job. The first is that the science is often in a state of flux. Toronto Sick Kids came out with a report. It had a fair hearing. The government followed with its plan that closely followed the science – they claimed anyway. But, after that, it was a cascade of people denouncing the government action. Some of it based on science. Some of it based on what people thought the science said. All sorts of ideas, realistic and otherwise, started popping up all over the place by people we hadn’t heard before, but no matter who they were, it only mattered what they said. And, damn it, what they said better have conformed to how we felt or else they weren’t experts at all. Suddenly, the average person on the street became public health expert – champion of their own domain.

You see, it’s not just the scientists’ expertise that matter here. Teachers are expert at teaching, and parents are expert at parenting, and you can’t tell a teacher or a parent that they don’t know what’s best for their students or children, right? And, let’s not forget that other scientists might say something else entirely.

This is exactly where we’ve ended up – some scientists on one side, and the other experts and scientists on the other. The science says one thing, the other ‘experts’ say something else, and what you have left are political decisions. Our politicians pick which experts to listen to and we judge them on those choices.

If you’ve been following this, Minister Lecce first said students should be learning hybrid. Then, parents lost their gaskets at the thought that they’d have to miss weeks of work to be home with their kids. So, the government signaled full day reopen, and parents and teachers lost their gasket. However, the government’s big mistake is that they never presented it as a binary choice. Parents could have small classes if the classes were divided by 2 and students came every other day. Or, kids could come every day and class sizes would remain unchanged. The political decision remains at that point of convergence, but the science defence was used rather than the trade off.

Now we have teachers, their federations and some parents say that it is unsafe to have classes of more than 15, which is not, of course, verified by science. There isn’t a number. Classroom space is variable and the whole bit. Teachers also don’t want hybrid teaching. The only option, in their view, is full day every day class capped at 15 students. It’s eating cake and having it too. It’s also not very realistic.

So, the next time you wonder why government is not following the science, remember this school reopen debacle. Scientists are good at science. Social scientists ought to be good at how people perceive public policy.